Scamicry: Are you deliberately putting your customers at risk?

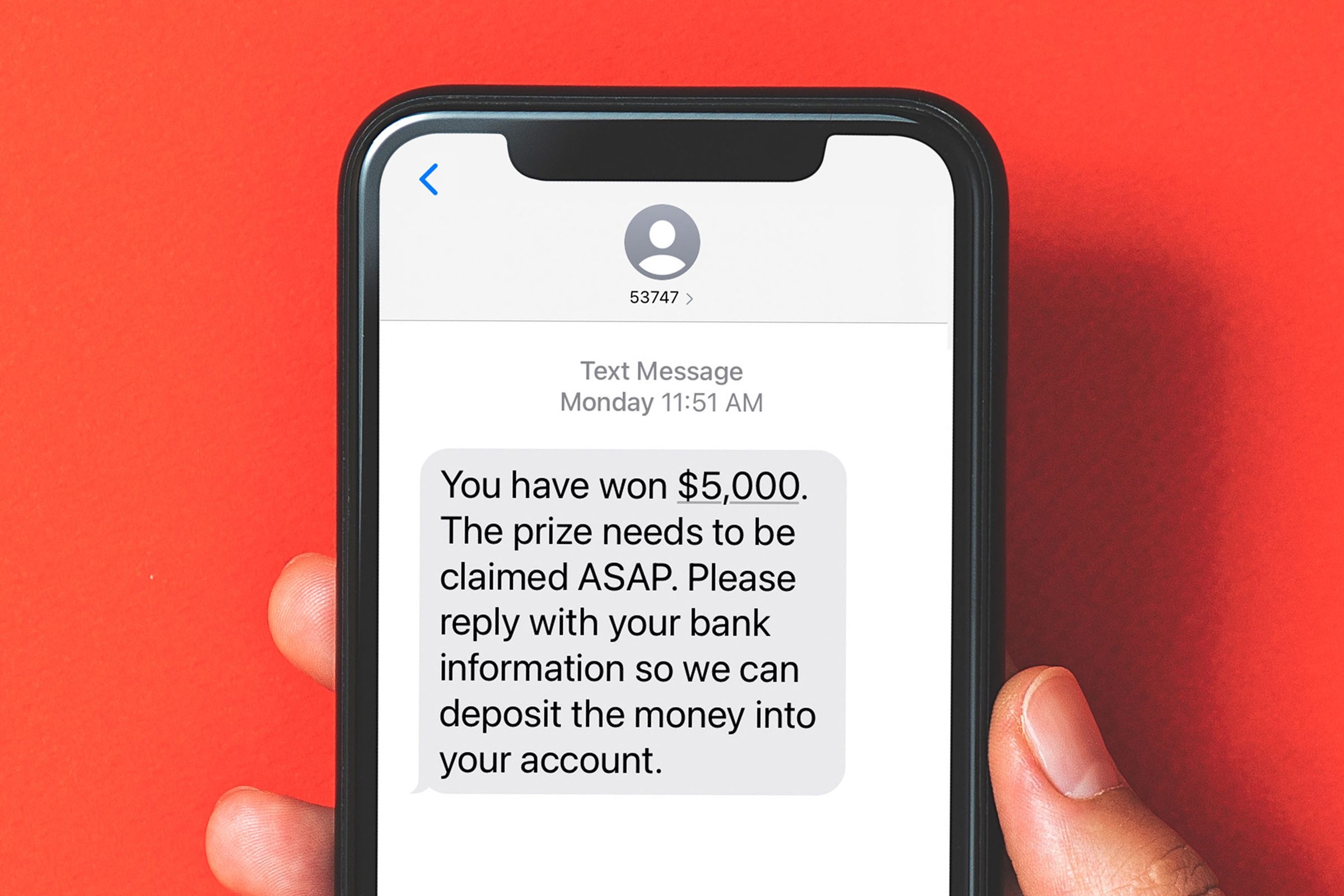

Figure 1: "Would you click?"

You're on holiday, far from home when a company you've a genuine and positive business relationship with sends an URGENT message.

Decide quickly! Is it a scam? Or should you click to find out more?

Choose wrong and you'll become a victim like Charlotte Cowles or Cory Doctorow as recently mentioned on Bruce Schneier's Cryrptogram.

Now surely, you'd expect your bank, hospital, or travel company to do everything in their power to make that choice easy? Surely you'd expect them to help you avoid being the victim of a phishing scam?

Then you'd be very, very WRONG!

And if you are part of a company, and you're involved in any way with security policy, please read on and carefully consider the ways you may be putting your customers at risk and helping cybercriminals.

A curious case of scamicry

As Troy Hunt writes this week in Thanks FedEx, This is Why we Keep Getting Phished maybe the company you are dealing with is grossly incompetent at security?

Imagine that you receive a notification that:

- comes from an unknown, withheld number

- comes from a no-reply email address from some weird origin that does not match the company domain

- is written in poor English with grammar and spelling mistakes

- contains dodgy looking links and incoherent urges to click them

- has out of date branding or poor quality images

- contains nonsensical reference numbers

But here's the twist… It's actually from them!!

Adam Shostak has a name for this. He calls it "scamicry": legit communications that mimic scams. Like if a company calls you and asks for your security details, but offers you no way to verify who they are first. Here, you can read Adam's notes from BlackHat 2018.

If you follow NCSC best practice to avoid phishing you'll immediately attempt to establish a communication with the company via a known legitimate link, initiated by yourself. You could visit their website or call them. Well good luck with that!!

As you know, it's impossible to speak to a human. You'll encounter layer upon layer of automated deflection, so-called customer service using AI voices and chat bots. You'll encounter "contact us" forms with broken HTML, dangerous JavaScript, more tracking code and cookie popups than you can shake a stick at.

You'll have to navigate endless greedy and unnecessary data gathering, jump over CAPTCHA puzzles and "security questions" and still the form will fail to send your message. If you're lucky that any human ever reads it, you may get a "timely response" in a few weeks or months.

Their dreadfully designed website will send you around in circles for hours, eventually asking you "Why not use our app?"…

Hmm, maybe because I'm not stupid enough to install another backdoor infested data harvesting tool on my already compromised smartphone from a company that appears to be ignorant about security?

If you were only in a state of high-anxiety about being scammed then certainly, after hours of dealing with inhuman gate-keeping and infuriating hold music, your mental health will now be in shreds. Better just to click the scam link under intolerable pressure.

So why is the standard anti-phishing advice that you'll read on the NCSC website or get from standard corporate training seminars about as much use as a chocolate teapot in the Sahara desert?

Here's why, and you won't find many people telling you this fact of modern life:

Because profit and security are in tension.

- It costs money to provide security for customers. Lots of money.

- Your security is an externality.

- It's cheaper for companies to pay fines and compensate customers than to fix things.

It's real!

Sorry for the spoiler, but as you probably guessed, the punchline of Troy Hunt's article is that the insanely dodgy communication he reported as a phishing scam was actually genuine!! It had come from FedEx.

The pattern for these scamimic security blunders is typical.

Your bank or some other service sends a suspicious messages through a wild and weird channel, usually a third party outsourced service, insisting that something is;

"Urgent. Immediately answer this form with your personal details or we will lock/close your account".

To any normal person who has the least security awareness this seems scammy, and is rightly ignored. But then a few weeks later a physical letter arrives explaining how "Your account has been closed". If you're lucky you'll be inconvenienced by hours of phone calls or travel. If you're unlucky you'll lose thousands of pounds.

Something similar recently happened to me. While attempting to set up an account I was thrown by a random email from a so-called "identity confirmation service" with a name that oozes all the legitimacy of a Chinese chicken delivery service. Its obdurate tone was dressed in fluffy, almost infantile corporate down-talk, vague insinuations and insistence that I immediately start uploading my personal documents to their "secure" website (I'll be the judge of that, thank you), and a presumptuous air that I should know who they were.

Everything about it yelled phishing scam! After deleting three such messages, I contacted the alleged company, and surprisingly verified that they really did want a verification. So I arranged an in-person meeting. Apparently it's all about KYC (Know Your Client). KFC more like. Kentucky-Fried Cybersecurity.

And it happened to our own Helen Plews. As you can hear in this Cybershow segment (time:42:20), she received a very dodgy SMS from a private number with all the hallmarks of a phishing scam. Following best practice, she called a listed organisational number, and was soundly punished for attempting to report a security problem.

Like the NHS, healthcare companies in the US send scammy looking links for payment processing, things like my-healthcare-billing.net.

Shoot the messenger

Punishing the customer for being vigilant about security seems ever more common. One correspondent explained how their bank website had a section about security. They helpfully showed the fingerprint of the TLS key (website security key that should give you a "green padlock"). Their own instructions clearly said: "If this key doesn't match, then please do call the bank." The keys didn't match. The customer dutifully called the bank… and promptly got their bank account locked. Resolution arrived after an expensive and time consuming visit to the branch. The fault was with the bank whose online website was outdated.

Another commenter got an email from the IT centre of her workplace, coming from a domain completely unlike the official company domain. Subject: "URGENT: your account is expiring", and containing multiple weird looking links in the email body, each an illegible multiple line scrawl of hexadecimal numbers. Exactly the kind of thing that immediately gets all the hairs on your neck jumping, and spreading down your spine like an Internet dance craze. I've had dozens of these and they all go straight to /dev/null (in the wastebasket). Turns out it was "real".

These come from the same 100k+ employee companies that send out punitive "phish-test" emails where anyone who clicks on the URL is destined for the "remedial training" naughty step.

You're screwed if you click, and you're screwed if you don't.

In another case a customer got sent "a badly-scanned letterhead" that was "very, very fishy." Could this be legit? Apparently so. The query was escalated up the security chain. Nobody in the company could "understand why it was bad."

Truth is, the security staff of most companies, right up to CISO level, are confused and conflicted. Their thinking is that - it's okay if we say it is, since we set the security policy. In a way that's true. Looming regulation aside, they're free to set their standards as low as they like.

More importantly the reciprocal is true. As a customer the one and only inviolable standard of whether your security is good enough is whether I feel it is. You have to convince me. Because it's not your security. It's mine.

Some cases and explanations

Back to practicalities, why do companies not just use their main domain for URLs? Aside from the fact that some browser makers unilaterally decided it would be more secure to hide URLs from 'stupid' users (ignorance is strength), if customers can see a recognisable domain that clears up most of the confusion.

Part of the problem is that companies like Google and Microsoft, with whom millions of people sadly still have email accounts, punish companies for sending "bulk mail". If companies use their main domain, their normal corporate email may get blocked by anti-spam filters. Instead they use a different, unrelated domain for bulk mails. Some of the better known companies like Mailchimp specialise in sending bulk mail and have "arrangements" with BigTech providers who now act as the gatekeepers of email. But even giant banks, in a bid to save a few pennies, will shop around and use some insanely dodgy third party providers.

The sad thing, as it relates to global economics, is that the profile of cheap outsourced messaging companies is similar to those who actually run scams. Indeed they may be the same companies. The work is done by low paid, factory-hen "IT" workers in developing countries. They hate their jobs and do the least work possible. But how else can we have sky-high salaries and massive bonuses for bank executives?

All of this is unnecessary because in fact most of these security messages are not "bulk email" at all. They are legitimate personal messages specific to a situation and sent to a single recipient. The charitable interpretation is that because they are templated, BigTech spam filters pick them up. Obviously trillion dollar US companies don't have the resources to tell the difference. A less charitable take is that giant tech monopolies are just squeezing everyone for cash. Remember, your security and their profit are always in conflict.

Regardless, scammers can spoof addresses and send messages through the company, making them look legitimate. AI tools can now clone websites of any company, perfectly and in moments.

Technical solutions

Why can't a recipient have certainty about the identity of who sent a message? Can't all this be fixed with technology? Surely there's some kind of cryptographic authentication system for text messages and emails and proper use of caller-ID for phone calls?

Indeed, we solved all of this in the 1980s. The truth is that most companies lack the expertise to use cryptographic signatures, or become enmeshed in proprietary "partnerships", for example with companies like Adobe whose solutions cannot be universalised. Additionally, most customers are not clear about what is really secure. They rely on the security advice of companies that are dishonest because they have their own profit motives.

For example, almost everyone wants you to install their "app" these days. Don't do that. The world wide web (WWW) was developed as a universal standard for the connected world. It has everything needed for secure commerce. Apps are closed programs that install themselves into your smartphone operating system. They are notorious for data harvesting and for backdoors and other security risks that do not come from a normal web browser. And now you need to manage a separate application for every company you do business with? No thanks! Besides, "apps" assume you have a smartphone, something that security conscious people and those mindful of their mental health are increasingly moving away from.

Why can't we get this right?

Even with infrastructure for public key cryptography (PKI) and transport layer security (TLS) in 2024 nobody can be sure if a message from their bank, doctor or kids school is real. This is a disgrace.

The principal problem comes from the profit motives of companies who;

- use the cheapest solution in all cases

- eschew tried and trusted open source inter-operable systems

- deliberately isolate themselves from customers

- place the security onus on the customer

- do not allow customers to insist on their own minimum security standards and methods

But Troy Hunt puts it far better than I can:

What makes this situation so ridiculous is that while we're all watching for scammers attempting to imitate legitimate organisations, FedEx is out there imitating scammers!

What can you do?

If you're a customer

As a top-level rule of thumb, if it isn't costing the company to provide you security assurances, they aren't.

Read the NCSC guidelines and ask for help if you are concerned. Sometimes when you're in a desert the best thing you can get is a nice cup of tea. And check against the latest scams known at Which consumer magazine.

We offer this additional advice:

Never respond to cold calls or emails from any organisations, even if you do have an established relation with them.

When picking up calls from unknown numbers. DO NOT SPEAK. Just wait quietly for a moment. A human operator knows you have picked up. Let them speak first. This is to do with voice cloning and other AI techniques scammers can now use.

Contact a company only through a publicly recognised number that you have established is legitimate.

Use the principles from Left of Bang, which we also teach at Boudica as part of our radical sceptical awareness programme. Trust your feelings at every step.

Never be embarrassed to say no. Scams rely on your ego. Check yourself. Say "no" politely and say confidently that you do not trust their security measures. No respectable security officer will ever doubt that.

If you encounter any pressure, threats, rushing, scorn or down-talking, hang up immediately. Do not even say goodbye.

If any services send you worrying communications, from dodgy looking sources, or with words like URGENT and SECURITY RISK, just ignore it. Delete it. Move on as quickly as possible without anxiety. Let the problem escalate, It's their problem. In most legal contexts here in the UK the onus is not on you to resolve or respond to unless you get a physical letter delivered or served in person with a letter.

Sending physical correspondence is costly to scammers who generally play the numbers game. But if you have a reason to feel you may be targeted, treat any physical correspondence as if it were a phone call. Letterheads are as easy to forge as a website. Never use any information in the letter. Contact the company separately and establish a completely separate chain of correspondence.

If necessary buy a £10 "burner phone" from a high-street pawn shop and insist all communication on the matter go through that new number.

Genuine companies with real security concerns will attempt to contact you in multiple ways and if sincere will provide a method that gives you assurance that satisfies your requirements, not theirs. Never call back on a number or email address that they give you.

The aim is to open a channel through a public end-point. These include a TLS secured public website, a general enquiries phone number published on an authentic website, or best of all an in-person meeting with a representative at a high-street office or an address given in the company's public listings.

Do not be intimidated. Some scammers are persistent and will make threats of debt collectors and so on. If you are harassed, find a solicitor who specialises in security escrow and direct all communication through them. Scammers will quickly give up at that point. Legitimate companies will take the matter seriously and it will be quickly resolved with little cost - but far less than you risk losing in an internet banking scam.

If you're a company

Security is a quality issue. If you're still letting IT run your customer facing quality you need to restructure and put that under quality management.

Pay someone to answer your phone. It's the least measure of good will and politeness in the modern world. "All our operators are busy right now…." No they aren't. Everybody knows that, and the moment anyone hears it your reputation is mud. If you keep any personally identifiable information (PII) or have customers with accounts, have a number specifically for security.

Start by reading Security Engineering by Ross Anderson It's an accessible, and addictively interesting book that CISOs can understand.

If your company needs help, you are welcome to talk to us at Boudica Cybersecurity. We will train you and your staff in advanced craft, psychology and cryptographic methods to make trustworthy connections with your customers. It won't cost you the Earth, but it may save your reputation.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks are due to Troy Hunt for the fine article that seeded this post, and to the many contributors of Hacker News and Cryptogram for insights into this perennial problem.